Eggs were once a staple of a healthy American breakfast. But over time, they’ve acquired a complicated assortment of contradictory recommendations.

In the 1960s, the American Heart Association said people should eat no more than three egg yolks per week to limit the intake of cholesterol, a contributing factor in cardiovascular disease. A March 1984 TIME Magazine cover featured a plate with a bacon-and-fried-eggs frowny face.

In the 1990s, the Egg Nutrition Center responded by showing the nutritional benefits of eggs, including high-quality protein, which promotes healthy growth and development in children as well as keeping consumers feeling full longer; lutein and zeaxanthin, which lowers risks for macular degeneration, cataracts, atherosclerosis and some types of cancer; and choline, which plays an important role in fetal and neonatal development.

Eggs seem to have bounced from “don’t eat” to “eat” and back more than any other food. Earlier this year, another study claimed that the more eggs a person eats, the more likely they are to get cardiovascular disease and die early. In addition, eating eggs also has been linked to an increased risk of diabetes.

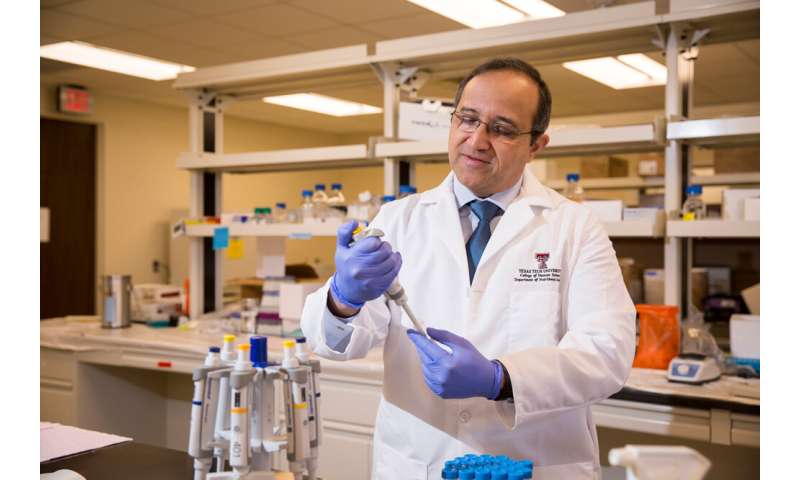

While such observational studies point at an association, they don’t prove that eggs cause these conditions. Researchers at Texas Tech University are showing that eggs may not deserve the scrambled reputation they’ve gotten.

Nik Dhurandhar, Helen Devitt Jones Endowed Professor and chair of the Department of Nutritional Sciences; John Dawson, an assistant professor in the department, and Samudani Dhanasekara, a doctoral candidate in the department’s Obesity and Metabolic Health Lab, set out to determine the relationship between eggs and foods because this relationship may influence cardiovascular disease or diabetes. They tested if eggs are eaten with saturated fat, which may increase cardiovascular disease risk, and they determined whether eggs deteriorate the body’s handling of glucose, which may indicate an eventual increase in the risk for diabetes.

“For healthy human beings, there’s no limitations for egg consumption,” Dhanasekara said. “It is a good source of protein that can be easily added to a person’s meal.”

Dhurandhar, Dawson and Dhanasekara conducted two experiments using the same 48 adult subjects. In the first experiment, participants ate normally and prepared their eggs in any way they chose. Researchers used the Remote Food Photography Method, which is a novel way to determine food intake without relying on people’s memories to accurately recall what they ate. The study participants were provided a cell phone to photograph every meal before starting and after finishing, and the photos were sent to a central analysis facility to determine the amount and type of food participants ate.

The results showed that eating eggs did not equal higher saturated-fat intake, although Dawson cautioned that different preparation methods—such as frying in butter—would make a difference.

“The stereotypical egg breakfast isn’t just eggs: It has foods with a lot of saturated fat, such as bacon and sausage,” Dawson said. “But do these have to be eaten together? No.”

In the second experiment, the researchers examined whether eating eggs worsened glucose levels. The participants were randomly assigned to eat certain breakfasts—breakfast with scrambled eggs, breakfast with saturated fat, scrambled eggs with saturated fat, or a control meal—that were designed to have the same number of calories and the same amount of fat, carbohydrates and protein.

The results showed that eating eggs had no significant adverse effect on blood glucose levels. Also, additional analysis of those who routinely ate greater numbers of eggs versus those eating fewer eggs revealed no difference between glucose levels.

“Collectively,” Dhurandhar said, “these results do not support the conclusions drawn from the observational studies published earlier.”

[“source=medicalxpress”]